Dear Friends,

Today is the 100th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in New York City, a horrific illustration of the conditions immigrant workers endured — and continue to endure — in garment industry sweatshops.

It’s a piece of news that I first learned from a poem, many years ago. Robert Pinsky weaves this bit of history into his ode to the shirt, from his 1990 collection The Want Bone.

It’s nearly that time of year again — National Poetry Month is just around the corner — so I thought I’d send you this little appetizer, because today is the anniversary, and also so that you can let me know before next week if you’d like to be on the poem-a-day list this year. And if you have any friends or family who would like to be added (or removed), please send them my way!

I will send out one poem each day from April 1-30. No prior poetry experience is necessary to participate! Enthusiasm, ability to read (mostly English), and access to email are the main prerequisites.

So, if you have a minute, take in “Shirt.” And then take a minute to take in your own shirt, whatever you happen to be wearing right now — try to figure out how many cuts of fabric were sewed together to make it, how many buttons, how many stitches; if you don’t already know what it says, take a minute to read your shirt’s tag, the whole tag; think of words you’d use to describe its color, texture, size or fit. Put yourself in Pinsky’s sleaves for a minute, and imagine the moment you realized you were wearing a poem.

To learn more about National Poetry Month, visit www.poets.org, the website of the Academy of American Poets.

You can also read more about the Triangle Factory Fire here.

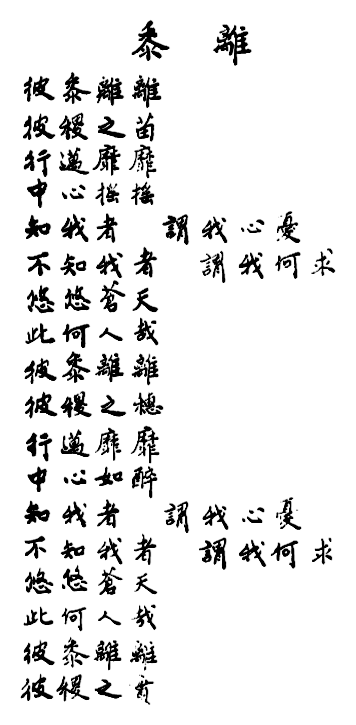

Shirt

The back, the yoke, the yardage. Lapped seams,

The nearly invisible stitches along the collar

Turned in a sweatshop by Koreans or Malaysians

Gossiping over tea and noodles on their break

Or talking money or politics while one fitted

This armpiece with its overseam to the band

Of cuff I button at my wrist. The presser, the cutter,

The wringer, the mangle. The needle, the union,

The treadle, the bobbin. The code. The infamous blaze

At the Triangle Factory in nineteen-eleven.

One hundred and forty-six died in the flames

On the ninth floor, no hydrants, no fire escapes—

The witness in a building across the street

Who watched how a young man helped a girl to step

Up to the windowsill, then held her out

Away from the masonry wall and let her drop.

And then another. As if he were helping them up

To enter a streetcar, and not eternity.

A third before he dropped her put her arms

Around his neck and kissed him. Then he held

Her into space, and dropped her. Almost at once

He stepped to the sill himself, his jacket flared

And fluttered up from his shirt as he came down,

Air filling up the legs of his gray trousers—

Like Hart Crane’s Bedlamite, “shrill shirt ballooning.”

Wonderful how the pattern matches perfectly

Across the placket and over the twin bar-tacked

Corners of both pockets, like a strict rhyme

Or a major chord. Prints, plaids, checks,

Houndstooth, Tattersall, Madras. The clan tartans

Invented by mill-owners inspired by the hoax of Ossian,

To control their savage Scottish workers, tamed

By a fabricated heraldry: MacGregor,

Bailey, MacMartin. The kilt, devised for workers

To wear among the dusty clattering looms.

Weavers, carders, spinners. The loader,

The docker, the navvy. The planter, the picker, the sorter

Sweating at her machine in a litter of cotton

As slaves in calico headrags sweated in fields:

George Herbert, your descendant is a Black

Lady in South Carolina, her name is Irma

And she inspected my shirt. Its color and fit

And feel and its clean smell have satisfied

Both her and me. We have culled its cost and quality

Down to the buttons of simulated bone,

The buttonholes, the sizing, the facing, the characters

Printed in black on neckband and tail. The shape,

The label, the labor, the color, the shade. The shirt.