Emerging fair from out her torn green dress,

Is beauteous in the garden for her hour,

As Yusuf in his youthful loveliness.

Go, breeze of spring,

Haste to tell Yakub, blinded by his tears,

The tidings that shall end his sorrowing

And lift the darkness from his troubled years.

Hello Friends,

Could you tell that today’s poem excerpt was a translation as you were reading it? We have very few translations of the princess and poet Zeb-un-Nissa’s work from Persian to English; this 1913 translation is by Magan Lal and Jessica Duncan Westbrook, and the style of the translation has a lot more in common with 1900s English poetry than the 1600s Persian poetry of the original. To give you an example of how translations can differ, the same excerpt has also more recently been translated by Lisa Sarasohn as:

Blooming, her beauty makes the garden beautiful.

Like Joseph, her loveliness perfumes the air.

Spring breezes, go. Take the news to Jacob, end his sorrow

for the loss of son, wipe darkness from his eyes,

lift the troubles that have weighed upon his spine.

As you can see, it’s very difficult to capture both the poetic form and a poem’s meaning from another language. But key images, like the flower bud tearing through a green dress, persist from the original author. (I’ll let you in on a little secret: Sometimes one image is so good I will pick a poem to share with you just for that one image — today’s torn green dress is one of those.)

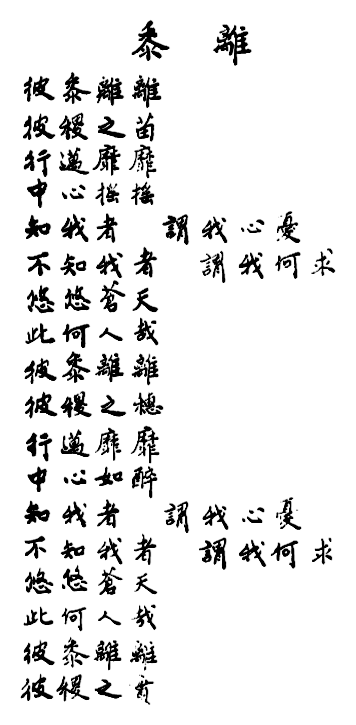

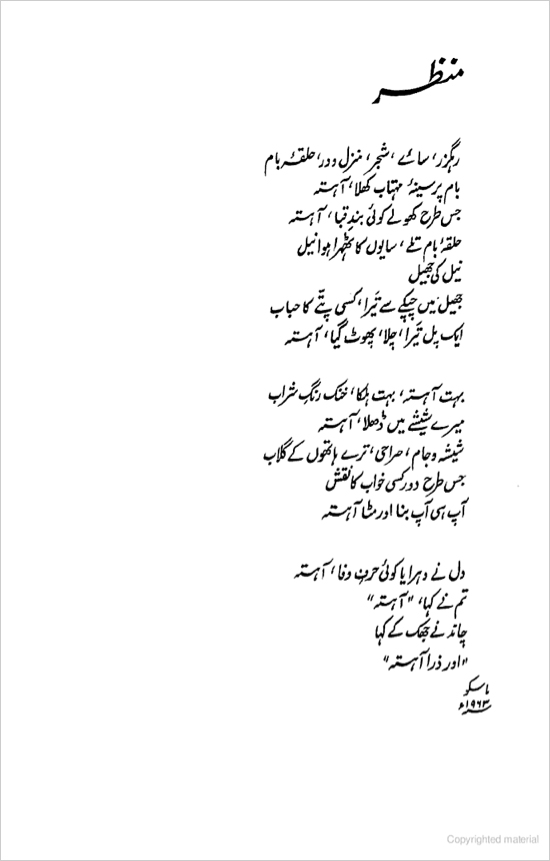

What you are largely missing here in translation is Zeb-un-Nissa’s use of form. The ghazal is a difficult poetic form with roots in seventh-century Arabia. Each couplet in a traditional ghazal is its own self-contained poem. The first couplet establishes an end-rhyme, and the second lines of all the succeeding couplets continue this rhyme. The last couplet traditionally contains a reference to the poet’s name — it’s a signature of sorts; Zeb-un-Nissa used the pen name Makhfi or “Hidden One” to reference herself.

As if the ghazal form weren’t difficult enough, a diwan is a sequence of ghazals, ordered according to their rhyme. Sarasohn explains, “The first group of ghazals rhymes with the first letter of the alphabet, the second group rhymes with the alphabet’s second letter, and on down the line.” The excerpt above, ghazal XIV, is from The Diwan of Zeb-un-Nissa.

One of the sad facts of literature is that you pretty much have to have been a princess or a queen for your writing to have survived from the 1600s if you were female. Zeb-un-Nissa is one of those figures whose words have made it to us — a princess from a time when the Mughal or Mogul Empire ruled the Indian subcontinent. A few details from her biography that may be relevant to understanding her as a poet: Zeb-un-Nissa became a Hafiza — meaning “guardian” or “memorizer” — at age seven, meaning at seven years old she had memorized and could recite the entire Quran (114 chapters made up of over 6,000 verses). She was deeply influenced by Islam and the Quran, and nearly all her poetry is religious in content. She never married — some say because she was married to Allah, some say she had affairs with mortal men. Lastly, for reasons that are still debated, Zeb-un-Nissa’s own father (the emperor) imprisoned her for the last 20 years of her life. It is believed that these ghazal were written during those years of imprisonment.

That was a lot of me writing for just a little bit of Zeb-un-Nissa! Apologies if I got a little too carried away in explanations here. But I hope you maybe still got something out of it.

— Ellen

P.S. For a very different interpretation of the ghazal form (in contemporary English, rather than seventeenth century Persian) — and one of my favorite poems of all time — see “Ghazal” by Emily Moore.