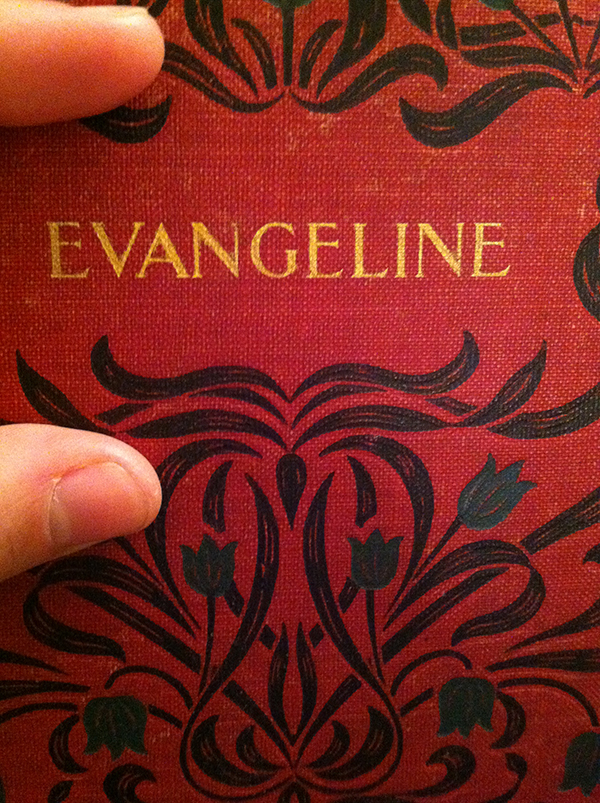

There’s something very special about holding a 114-year-old book in your hands, that visceral reminder of how long these words have lasted, and how precious these words’ surviving is.

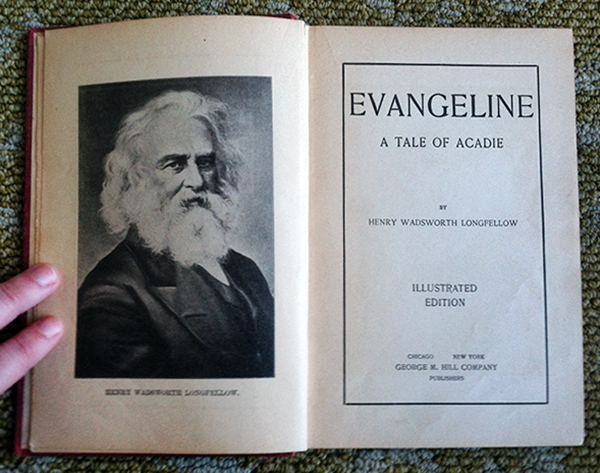

This 1900 edition of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s (167-year-old) epic poem Evangeline that Bethany gave me has been in Long Beach at least since its previous owner inscribed it in pencil in 1926. A number of poems this month will come from books that were gifts from one of you on this poetry list, actually — the most precious books in my poetry collection.

Longfellow’s epic is a very readable page-turner: His title character, Evangeline, loses her family, her childhood home, everything she’s ever known, when the British forcibly remove the French population from Acadia (now Nova Scotia). We then get a historical tour of pre-Revolutionary America that covers territories from Louisiana to Nebraska to Michigan to Pennsylvania, as Evangeline spends her life searching towns where scattered survivors from Acadia may have settled, trying to find her long-lost love Gabriel.

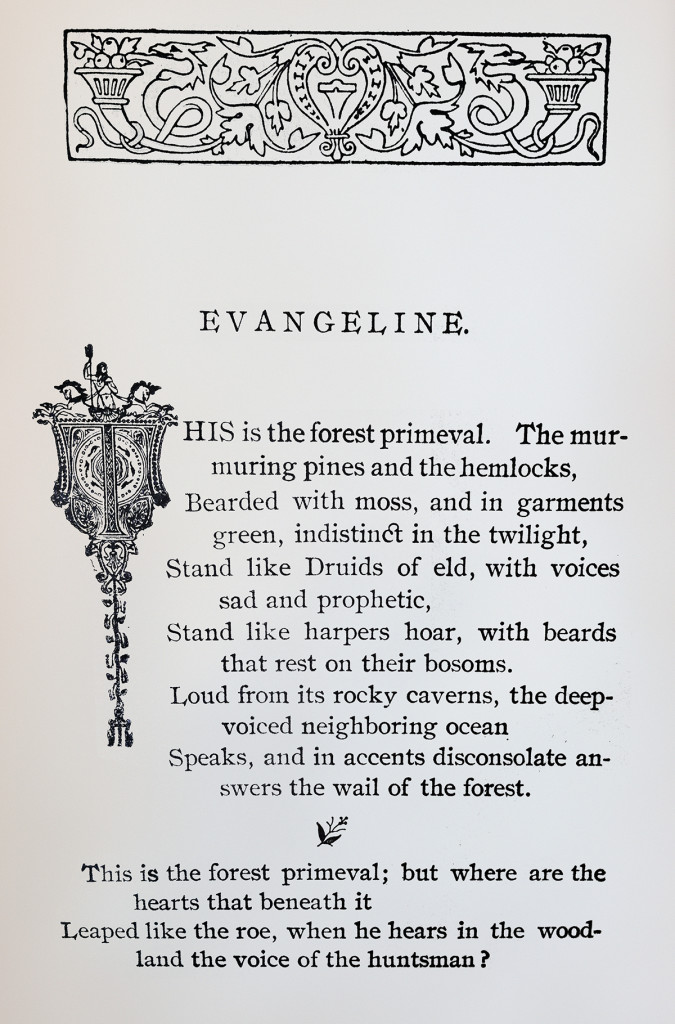

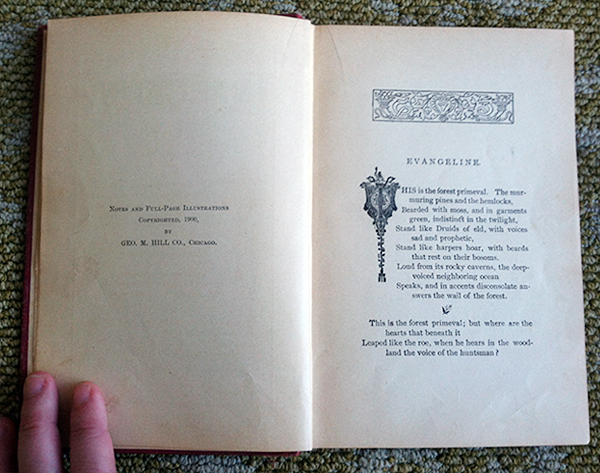

Today’s poem is also an exercise in whether the printed page matters, especially for poetry. Whether font matters. Margins. Page breaks. The poem that came before a poem or after a poem when it was bound as a collection. A poet may not have personal control over all those aspects of print, but do they still impact how you read a poem? Take a look at the photos below of my 1900 copy of the famous opening lines of Evangeline, and then check out the 2014 version of Evangeline on poets.org, the website of the Academy of American Poets, who officially bring you National Poetry Month.

Make an argument for how these are or are not the same poem. Make an argument for whether paper books, electronic books, or some other form of the written or spoken word will survive the longest on this earth. What does a 114-year-old copy of a book written in 2014 look like?