Dear Friends,

First off, I have a correction to the April 5 poem-a-day: It turns out that the current year is 2010, not 2261, and therefore Kozan Ichikyo’s 1360 verse has not been remembered “over 900 years later” — at least not yet. My apologies for the error; I switched monks on you at the last minute and failed to update that figure!

Now, today’s poem: comes to us from Faiz Ahmed Faiz, a prominent figure in Punjabi literature and politics and a best-selling modern Urdu poet in both India and Pakistan. This translation is by Naomi Lazard, who collaborated with Faiz to refine her translations of his selected works until his death in 1984.

Be Near Me

Be near me now,

My tormenter, my love, be near me—

At this hour when night comes down,

When, having drunk from the gash of sunset, darkness comes

With the balm of musk in its hands, its diamond lancets,

When it comes with cries of lamentation,

with laughter with songs;

Its blue-gray anklets of pain clinking with every step.

At this hour when hearts, deep in their hiding places,

Have begun to hope once more, when they start their vigil

For hands still enfolded in sleeves;

When wine being poured makes the sound

of inconsolable children

who, though you try with all your heart,

cannot be soothed.

When whatever you want to do cannot be done,

When nothing is of any use;

—At this hour when night comes down,

When night comes, dragging its long face,

dressed in mourning,

Be with me,

My tormenter, my love, be near me.

Okay, now I’m going to do two things to you:

1) I’m going to switch translators on you. I tend to prefer Naomi Lazard’s translations of Faiz’s works. However, partly as an excerise in experiencing just how much of a different feel two translators can give you for a poem, I’m also including a more recent translation by the Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali below.

2) I’m going to tell you something about the address “my love.” Addressing a poem to “my love” or “the Belovéd” (depending on your translation) is a staple of Urdu poetic tradition, and often carries meanings of lover or dear friend and of God. In addition to those meanings, Agha Shahid Ali makes a compelling argument that Faiz also intends to invoke a political meaning of “the Movement” or Marxist revolution for “the Belovéd.” Ali writes, “The reader begins to infer, through a highly sensuous language, that waiting for the revolution can be as agonizing and intoxicating as waiting for one’s lover.”

So here we go with translation number two:

Be Near Me

You who demolish me, you whom I love,

be near me. Remain near me when evening,

drunk on the blood of the skies,

becomes night, in its one hand

a perfumed balm, in the other

a sword sheathed in the diamond of stars.

Be near me when night laments or sings,

or when it begins to dance,

its steel-blue anklets ringing with grief.

Be here when longings, long submerged

in the heart’s waters, resurface

and everyone begins to look:

Where is the assassin? In whose sleeve

is hidden the redeeming knife?

And when wine, as it is poured, is the sobbing

of children whom nothing will console—

when nothing holds,

when nothing is:

at that dark hour when night mourns,

be near me, my destroyer, my lover,

be near me.

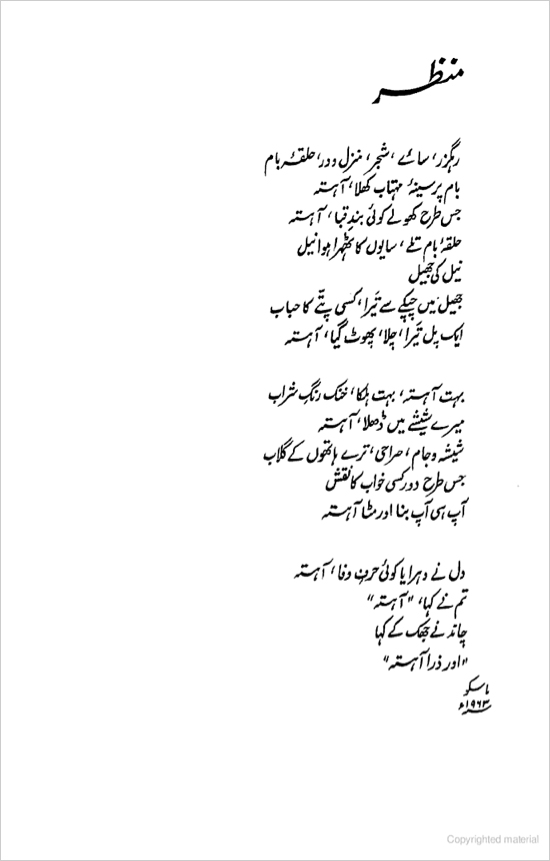

So which translation do you prefer? Do you think which version you read first impacts that feeling? Can anyone speak to how each translation compares to the original (below)?

Does the poem read differently to you once the thought is planted that “the Belovéd” could mean “the movement” or “the revolution”? Did you infer, or do you think you could have inferred, that meaning in the translation or in the original without it having been suggested?

If you’re not quite quenched, see Faiz’s “Before You Came” for one more glass of wine and “When Autumn Came” to let one bird sing.

Best,

Ellen